For many Tunisians, shortages of essential foods, fuel and key farming products linked to the war in Ukraine, have tested them to the limit, they’ve been telling UN News.

“There is no sugar, I have to take a taxi very far away to buy one kilogramme of sugar,” one woman explains in frustration, at a market in Kairouan, a town several hours drive south of the capital, Tunis.

“The prices are going up! Poor people can no longer afford anything. It is like the world is on fire,” another woman explains, as she opens her purse to pay for a bagful of tomatoes, jumbled together on a wooden cart by the side of the road.

Surprise appeal

Nodding his head in agreement, the stallholder takes her money and makes an astonishing, if discreet, appeal. “Please, make it easier for us to migrate across the sea, so we can leave,” he says.

Although the elderly customer scoffs at the idea – “He wants to drown! He wants to drown!” – for many younger Tunisians, leaving the country in search of work and security is a frequent topic of conversation.

This is despite the fact that many thousands of people have died trying to cross the Central Mediterranean Sea from North African nations to Europe on unsafe boats in recent years, and regular TV news reports that announce yet another missing person - or family - at sea.

Migration pressures

“I think what the crisis in Ukraine has brought up again, is the hard choices that people have to make on a daily basis, because people forced to flee their homes, people forced to flee their country, are not taking that decision lightly,” says Safa Msehli, spokesperson for the International Organization for Migration (IOM).

For many Tunisians, it remains a challenge to source basic staples, although more than 85,000 metric tonnes of Ukrainian wheat have arrived in Tunisian ports in the two months since the Black Sea Grain Initiative kicked into action, its Joint Coordination Centre in Odesa, said on Thursday.

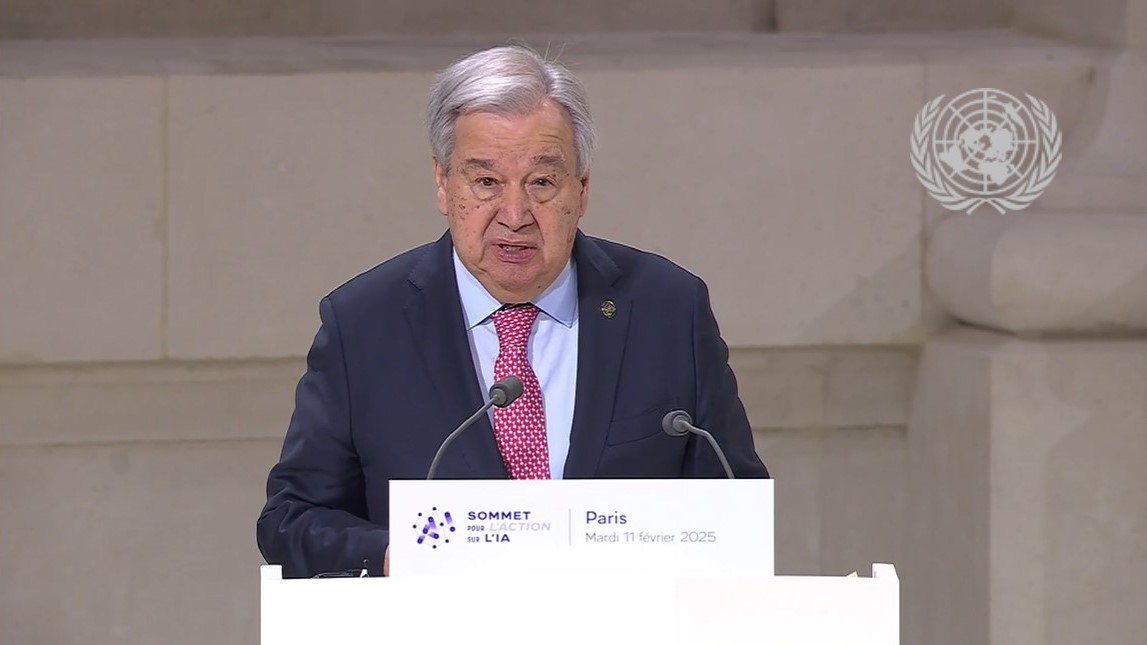

The agreement was described as a “beacon of hope” by UN Secretary-General António Guterres at the signing ceremony for the Black Sea Grain Initiative on 27 July in Istanbul, with representatives from Russian and Ukraine.

Since 1 August, 240 vessels have sailed from Ukrainian ports with some 5.4 million metric tons of grain and other foodstuffs.

Spreading the load

At an enormous mill in the Tunisian capital, there’s an abundance of flour, as workers stand under a conveyor belt which transports an apparently endless supply of semolina, packaged up into large, heavy-duty plastic sacks.

As the bags start to fall, the men grab them in turns and load them into a large flat-bed lorry until it is full, their faces covered in fine white flour.

The scene is industrious, but the mill is not nearly as busy as it should be, thanks in no small part to the impact of the Ukraine conflict on cutting grain exports from Black Sea, and its role in accentuating existing economic uncertainty.

“Now, we are not in crisis, the crisis is always happening,” says Redissi Radhouane, the chief mill operator at La Compagnie Tunisienne de Semoulerie. “When we look for the wheat, we don’t find any. The wheat is not abundant like before.”

‘It’s like hunting without bullets’

At a wholesaler’s outlet in Mornag, a town on the outskirts of Tunis, customer Samia Zwabi knows all about the shortages and rising prices.

She explains to UN News that she has to borrow money or buy goods on credit for her grocery store, assuming she can find them in the first place. Like many parents, the fact that it’s the start of the school year is an additional concern.

Half capacity

“We are working at half capacity,” says Samia Zwabi, who reels off a wishlist that includes milk, sugar, cooking oil and fruit juice. “When a client comes, he can’t get all the basics. Clients ask for something I don’t have. We have no options. We need to be able to work to feed our kids.”

Echoing that message, wholesaler Walid Khalfawi’s main headache is the lack of available cooking oil, as his bare storerooms indicate. Another growing worry is the number of customers who pay on credit, he tells us, as he waves a thick wad of handwritten IOU chits.

“If a grocery owner comes here for cooking oil and finds it, he’ll automatically buy pasta, tomatoes, couscous and other products,” says the married father-of-three. “If he doesn’t find it, he won’t buy anything…It’s like going into the forest to hunt with your rifle but you have no bullets. What can you do?”

Sole breadwinner

From her modest single-storey home in the city of Kairouan, Najwa Selmi supports her family making traditional handmade bread patties known as “tabouna”, twice in the morning and once in the evening.

The process is laborious and time-consuming, a batch of eight flat rolls taking around 15 minutes to knock into shape from semolina flour, water, yeast and a drop of olive oil.

Once prepared, Najwa wets the surface of the soft patties and slaps them into the inside of a concrete oven that’s been stoked with firewood outside. She grimaces in pain as she removes them with her scorched hands, once she’s satisfied that they’re cooked.

The bread is delicious and Najwa has loyal customers, but it is not easy getting hold of a regular supply of flour, she tells us.

Classroom blues

“My youngest daughter will start school soon and I haven’t bought her anything yet, no bag, no books, no school stationery, no clothes,” she says. “If for any reason I had to stop working …or if I got sick, we do not know what the future holds, my family will be hungry, what will they eat?

“From where will they get the money? We do not have another alternative source of income.”

In the bustling Tunis neighbourhood of Ettadhamen, bakery owner Mohamed Lounissi is open about the stresses and challenges of keeping his business afloat, thanks to chronic shortages of flour caused by the war in Ukraine.

“For us, it’s a big problem, if I order eight tonnes, they only give me one tonne. They say you need to wait and then when I tell them I can’t work and I might close, they say, ‘Ok, close, it is not our business!’”

Essential oils

For olive grove and cereal farmer Inès Massoudi, the Russian invasion of Ukraine this February is just the latest in a series of problems that are beyond her control, coming after five years of failed rains and two years of economic uncertainty caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

In particular, she worries that everything she needs for her 50-hectare holding in Beja is now more expensive – and more scarce - than before the war.

Never mind having to pay for more expensive grain for planting, without pesticides to treat common wheat fungus, along with fertilizer to promote growth – a key Russian export before the war - Inès’s harvest could be down by as much as 60 per cent.

“My farm is part of the world and it feels it when something happens outside,” she says of her 50-hectare holding, where olive trees stretch away into the distance in a green haze.

Ahead of the upcoming planting season, “everybody is hesitating”, Inès continues, “because the cost of planting the wheat today is the equivalent of a car, or a new apartment…There is also the crisis in Ukraine that made the cereal prices increase, along with the prices of agrochemicals and fertilizers which have become very expensive.”

Feeling the heat

Back in Tunis, in the bustling Ettadhamen neighourhood, baker Mohamed Lounissi accepts that he is struggling. “It is a daily challenge,” he explains:

“There are no goods and raw material at all; it is (all) too little: no flour, no sugar, oil is not available all the time, everything is not available all the time, along with the price increase, the prices have increased terrifically, they are big increases.”

Standing in front of a sweltering bread oven that he worries he might lose his livelihood, unless he can repay his mortgage, Mohamed concedes that the stress of running a business in the current situation is getting to him. “If I don’t get the raw material I can’t work and I feel that I have a big responsibility in terms of paying the workers.”

In an outdoor storeroom, Mohamed shows us his meagre supply of wheat flour – a small pile of sacks barely reaching knee-height. He carefully locks the door on leaving, quietly chiding himself for not doing so earlier.

Getting hold of the precious ingredient “is a big problem”, he says. “If I order eight tonnes, they only give me one tonne. They say you need to wait and then when I tell them I can’t work and I might close, they say, ‘Ok, close, it is not our business!’”

Celebrity Media TV

Celebrity Media TV