Despite strong evidence that human activity played a role in catastrophic weather events, and the emergence of a fuel crisis sparked by the war in Ukraine, greenhouse gas emissions continued to rise. Nevertheless, the UN kept the climate emergency high on the international agenda, reaching major agreements on financing and biodiversity.

At the end of 2021, when the UN climate conference (COP26) wrapped up in Glasgow, none of those present could have suspected that a war in Ukraine would throw the global economy into turmoil, convincing many nations to suspend their commitments to a low carbon economy, as they scrambled to reduce their dependence on Russian oil and gas supplies, and secure fossil fuel supplies elsewhere.

Meanwhile, a host of studies pointed to the continued warming of the Earth, and the failure of humanity to lower carbon emissions, and get to grips with the existential threat of the climate emergency.

Nevertheless, the UN continued to lead on the slow, painstaking, but essential task of achieving international climate agreements, whilst putting sustained pressure on major economies to make greater efforts to cut their fossil fuel use, and support developing countries, whose citizens are bearing the brunt of the droughts, floods and extreme weather resulting from man-made climate change.

Record heatwaves, drought, and floods

The World Meteorological Organization (WMO) released a litany of stark reports throughout the year. A January study, announcing that 2021 had joined the top seven warmest years on record, set the tone for the year.

In Summer, when record heatwaves were recorded in several European countries, the agency warned that we should get used to more to come over the next few years, whilst Africa can expect a worsening food crisis, centred on the Horn of Africa, displacing millions of people: four out of five countries on the continent are unlikely to have sustainably managed water resources by 2030.

Whilst some regions suffered from a lack of water, others were hit by catastrophic floods. In Pakistan, a national emergency was declared in August, following heavy flooding and landslides caused by monsoon rains which, at the height of the crisis, saw around a third of the country underwater. Tens of millions were displaced.

Unprecedented floods in Chad affected more than 340,000 people in August and, in October, the UN refugee agency (UNHCR) declared that some 3.4 million people in west and central Africa needed aid, amid the worst floods in a decade.

A ‘delusional’ addiction to fossil fuels

In its October Greenhouse Gas Bulletin, WMO detailed record levels of the three main gases – carbon dioxide, nitrous oxide, and methane, which saw the biggest year-on-year jump in concentrations in 40 years, identifying human activity as a principal factor in the changing climate.

Yet, despite all the evidence that a shift to a low-carbon economy is urgently needed, the world’s major economies responded to the energy crisis precipitated by the war in Ukraine by reopening old power plants and searching for new oil and gas suppliers.

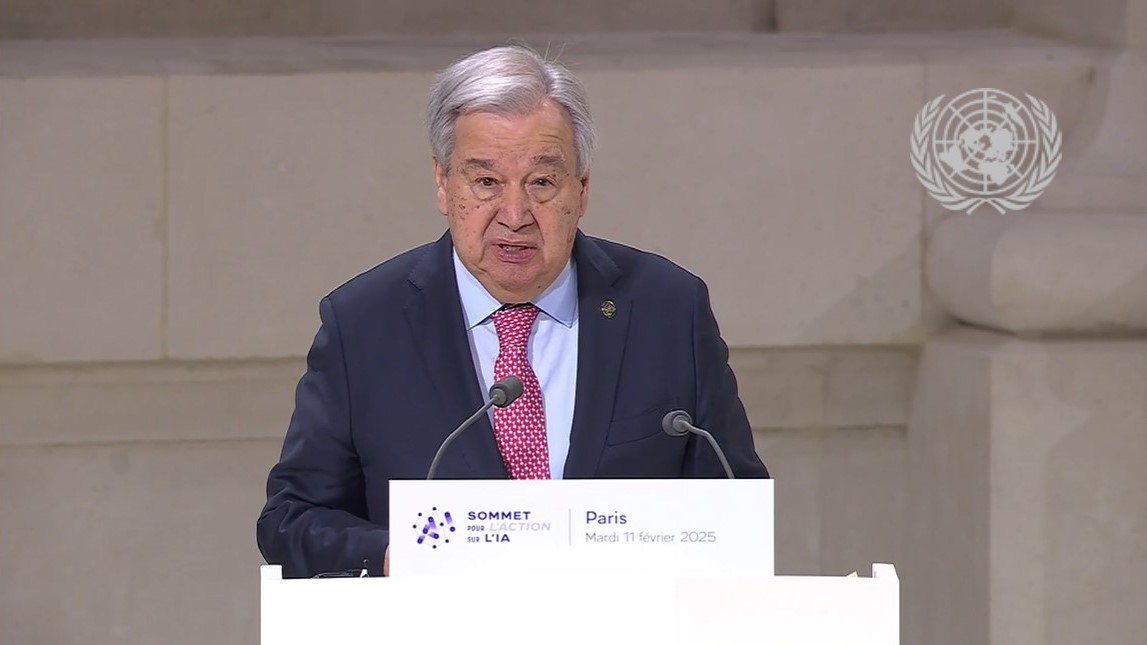

UN Secretary-General António Guterres decried their reaction, calling it delusional, at an Austrian climate summit in June, and arguing that if they had invested in renewable energy in the past, these countries would have avoided the price instability of the fossil fuel markets.

At an energy event held in Washington DC the same month, Mr. Guterres compared the behaviour of the fossil fuel industry to the activities of major tobacco companies in the mid-twentieth century: “like tobacco interests, fossil fuel interests and their financial accomplices must not escape responsibility”, he said “The argument of putting climate action aside to deal with domestic problems also rings hollow”.

Clean, healthy environment a universal human right

The July decision by the UN General Assembly to declare that access to a clean and healthy environment is a universal human right was hailed as an important milestone, building on a similar text adopted by the Human Rights Council in 2021.

Mr. Guterres said in statement that the landmark development would help to reduce environmental injustices, close protection gaps and empower people, especially those that are in vulnerable situations, including environmental human rights defenders, children, youth, women and indigenous peoples.

The importance of this move was underscored in October by Ian Fry, the first UN Special Rapporteur on the Protection of Human Rights in the context of Climate Change. Mr. Fry told UN News that the resolution is already starting to have an effect, with the European Union discussing how to incorporate it within national legislation and constitutions.

Breakthrough agreements reached at UN climate conferences

The year was punctuated by three important climate-related UN summits – the Ocean Conference in June, the COP27 Climate Conference in November, and the much-delayed COP15 Biodiversity Conference in December – which demonstrated that the organization achieves far more than simply stating the dire climate situation, and calling for change.

At each event progress was made on advancing international commitments to protect the environment, and reducing the harm and destruction caused by human activity.

The Ocean Conference saw critical issues discussed, and new ideas generated. World leaders admitted to deep alarm at the global emergency facing the Ocean, and renewed their commitment to take urgent action, cooperate at all levels, and fully achieve targets as soon as possible.

More than 6,000 participants, including 24 Heads of State and Government, and over 2,000 representatives of civil society attended the Conference, advocating for urgent and concrete actions to tackle the ocean crisis.

They stressed that science-based and innovative actions, along with international cooperation, are essential to provide the necessary solutions.

‘Loss and damage’ funding agreed, in win for developing countries

COP27, the UN Climate Conference, which was held in Egypt in November, seemed destined to end without any agreement, as talks dragged on way beyond the official end of the summit.

Nevertheless, negotiators somehow managed to not only agree on the wording of an outcome document, but also establish a funding mechanism to compensate vulnerable nations for the loss and damage caused by climate-induced disasters.

These nations have spent decades arguing for such a provision, so the inclusion was hailed as a major advance. Details on how the mechanism will work, and who will benefit, will now be worked out in the coming months.

However, little headway was made on other key issues, particularly on the phasing out of fossil fuels, and tightened language on the need to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius.

Enhanced biodiversity protection promised in Montreal

After two years of delays and postponements resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic, the fifteenth UN biodiversity conference, COP15, finally took place in Montreal this December, concluding with an agreement to protect 30 per cent of the planet’s lands, coastal areas, and inland waters by the end of the decade. Inger Andersen, the head of the UN Environment Programme (UNEP), described the outcome as a “first step in resetting our relationship with the natural world”.

The world’s biodiversity is in a perilous state, with around one million species facing extinction. UN experts agree that the crisis will grow, with catastrophic results for humanity, unless we interact with nature in a more sustainable way.

The deal, officially the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, includes impressive commitments, but these now need to be turned into action. This has been a major sticking point at previous biodiversity conferences, but it is hoped that a platform, launched at COP15, to help countries ramp up implementation, will help to turn the blueprint into reality.

Celebrity Media TV

Celebrity Media TV