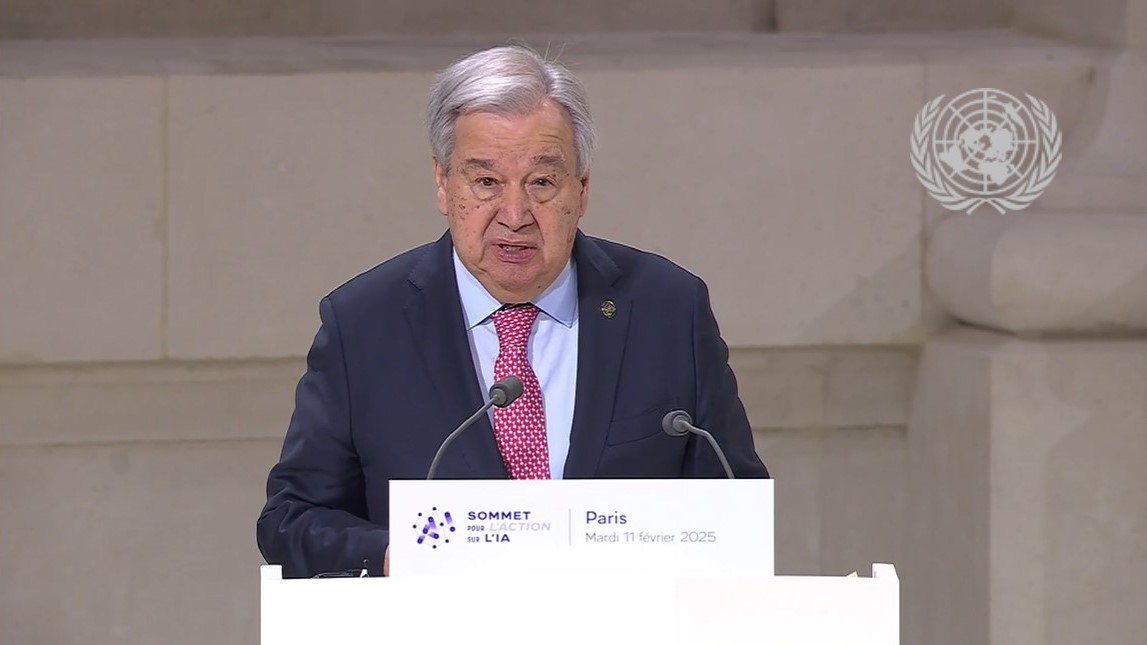

© IOM/Gema Cortés Aerial shot of Darien Gap.

© IOM/Gema Cortés Aerial shot of Darien Gap.

The Darién Gap, a dangerous route that links South and North America, has long been used by migrants trekking north to the United States, in search of a better life, or simply fleeing violence at home. As well as extreme physical challenges, they also risk attacks from smugglers, and other criminal groups.

With a bag full of hopes and dreams, Iriana Ureña, a 32-year-old Venezuelan mother of two, arrives at a Migrant Reception Station (ERM) in San Vicente, El Salvador, at the edge of the Darién Gap. The look in her eyes shows the pain of a mother who would do anything to protect her children.

Ms. Ureña and her husband Eduardo decided to take the journey north from Venezuela through the jungle with their two children in search of a better life.

The decision to leave their country, home, family, and friends, to start all over again, was a difficult but necessary one for them and many other migrants. They were hungry, dehydrated, and exhausted upon arrival at the station.

‘We saw ugly things along the road’

“The road was not easy, I felt that our lives were in danger. It was challenging because we saw very ugly things along the road, things that I would never think I would see in my life,” said Ms. Ureña.

According to Panama Migration Services, nearly 134,000 people, 80 per cent of whom were Haitians, risked their lives travelling through the dense jungle in 2021.

This is a record number of people crossing the 10,000 square mile rectangle of trackless jungle, rugged mountains, turbulent rivers, swamp, and deadly snakes, that spans both sides of the border between Colombia and Panama.

Today, the journey through the gap is made more perilous by criminal groups and smugglers who control the region, often extorting and sometimes sexually assaulting migrants.

However, the dynamics are changing, and Creole is heard less often in the jungle. Haitians are still trying to get from Colombia to the United States, but they are no longer the majority, and the Spanish of Venezuelan migrants, now prevails on the trail.

The numbers of Venezuelans crossing the Darién Gap in the first two months of 2022 (some 2,497), almost reached the overall total for 2021 (2,819). Venezuelans became the main group crossing the heart of the rainforest, but the data also shows Cubans, Haitians, Senegalese, and Uzbek nationals making the trip, among others.

High risk of violence

Emerging from the gap, most migrants pass through the Bajo Chiquito or Canaan Membrillo communities, before making their way on foot or by community boats, along the muddy waters of the Chucunaque River. The probability of suffering physical and psychological violence is very high throughout the whole journey.

For the International Organization for Migration (IOM) which is providing assistance to people in transit and host communities, in coordination with other agencies, and the Government of Panama, a perennial concern is securing enough funding for their lifesaving work.

"There is an urgent need to redouble coordination between governments and international cooperation to respond to the humanitarian needs of the population in transit.," says Santiago Paz, Chief of IOM Panama and Head of the Panama Global Administrative Center (PAC).

Among the newly arrived migrants is Johainy, a Venezuelan mother, and her one-year-old baby. “We faced a lot of difficulties, we were robbed, and saw dead people along the way”, she says. “Though we prepared ourselves as much as we could by watching many videos about the route, nothing could totally prepare us for what we experienced in the forest”.

“The migrants we assist in the ERM, are in a situation of extreme vulnerability and have very varied needs, from knowing in which country they are arriving, to medical assistance, clothes or basic hygiene products”, says Mariel Rodriguez, of IOM Panama. “The IOM team responds to these needs and coordinates with other Government agencies and institutions to ensure access to available services”.

Babel in the jungle

With a population of around 7,000 people, Meteti town has swollen in recent years with migrants – mostly Venezuelans, like Ms. Ureña, as well as Cubans, South Americans, Africans, South Asians, and others, all aiming for the United States or Canada.

For thousands of migrants around the globe the perilous, roadless jungle becomes a path of desperate hope to the north, in search of a better life. A babel of languages mixes in the vast jungle, from where some never emerge alive, though the actual death toll is unclear.

Migrants continue to stream through the Darién Gap, many with stories or signs of trauma, like Shahzad from Pakistan (“We found dead bodies and skulls during the walk”, he said) or Esther, who arrived exhausted, with blood-blistered feet, carried by other people.

Others arrived with stories of hope. “The hike was extremely hard. I went into labour and I had my baby in the middle of the forest, with only the help of my husband. I had to drink water from the river for days. However, the new arrival gave all the family a renewed sign of hope I did not expect," said Bijou Ziena Kalunga, 33, from the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Or tears of joy, as families are reunited after several days apart in the jungle, like Venezuelan William, Jorgeis, and their six-month-old baby. “I was really sad, and I kept praying for my husband to arrive. I can´t say how happy I am to have him back,” says Jorgeis.

Caring for migrants in Panama

- In recent years, the Panamanian government has put in place infrastructure to temporarily house people in transit, and attend to the humanitarian needs of this growing migrant population.

- With technical support from the IOM and other international organizations, Panama has installed three Migrant Reception Stations (or ERMs), where migrants find lodging and food, and where potential cases of COVID-19 are monitored.

- The San Vicente ERM was built by the Government of Panama together working through international cooperation, with the support of intergovernmental organizations, civil society, and the private sector.

San Vicente provides dignified conditions, in which physical separation and other biosecurity measures can be maintained to mitigate the spread of COVID-19.

Celebrity Media TV

Celebrity Media TV